- +216 71 772 000

- laboite@kilanigroupe.com

- Monday to Friday, 11am to 5pm.

Mohamed Ben Slama

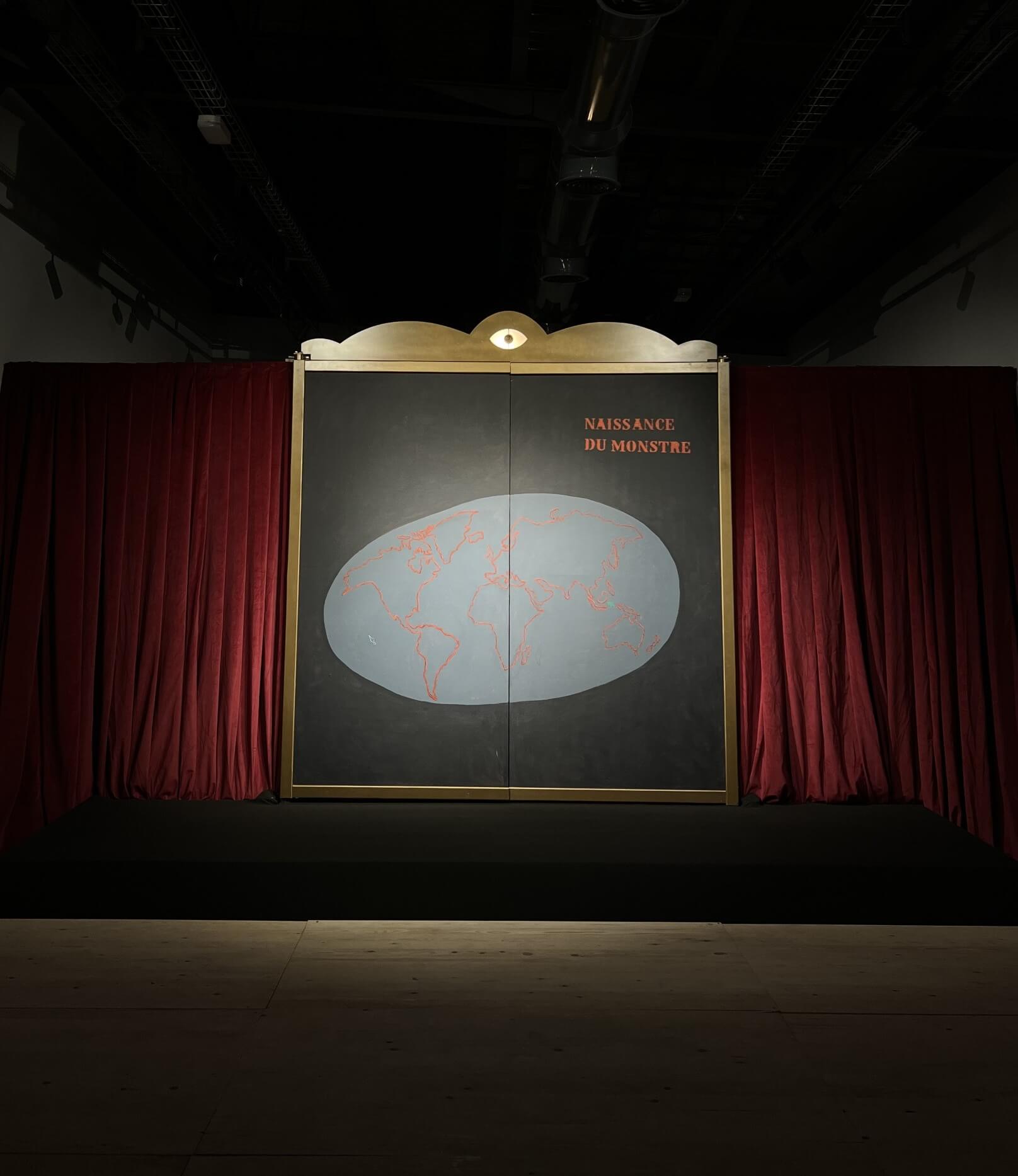

La Naissance Du Monstre

September 19, 2024 – January 17, 2025

La Boîte I Un lieu d’art contemporain

[…] Obviously they were talking about me and celebrating my captivity. Galloping monkeys and jocular satyrs seemed to be amused by this prisoner, stretched out and condemned to immobility.

But all the mythological divinities looked at me with charming smiles, as if to encourage me to bear the spell patiently, and all the eyelids slid into the corner of my eyelids as if to latch onto my gaze.

Charles Baudelaire, Le Théâtre de Séraphin.

Since the first pictures he painted at the age of fourteen, Mohamed Ben Slama has never abandoned his popular imagery. The ironic component it instills in his painting is in keeping with the contemporary subjects he deals with, while at the same time marking a distance from their socio-historical context. And for good reason: the subjects Ben Slama tackles are repeated, they make up the flesh of our humanity. How long has humankind made the world it has created uninhabitable? Ben Slama likes to call his paintings his “apocalypses”. His pictorial parodies of “Revelation” remind us that the idea of truth is only valid if lies are in power.

Political and social events are a social theater punctuated by narrative sequences of unveiling and revoicing. What sense would it make to produce so many plots without the help of an audience captivated by what they see, always quick to react? Ben Slama is well aware of this, and has chosen to set several of his paintings in small castelets with mechanical curtains that never fully open, so as not to break the hypnotic spell of what can only be partially seen.

The shutters of a large triptych entitled The birth of the monster. Tout comme la Vénus peinte par Botticelli, le monstre attend qu’on le regarde pour apparaître : autour d’une grande prêtresse ventriloque, une armée de personnages s’est rassemblée pour l’écouter, la défendre et la célébrer. Mais un grand désordre trahit la crédibilité de cette garde rapprochée. Leurs montures, leurs armes et leurs uniformes dépareillés font écho à la prêtresse ventriloque dont l’identité passe d’un corps à un autre, sans jamais se fixer. Qui est le monstre ? Dans quels corps se loge-t-il ? Qui sont ses intercesseurs, dirait Deleuze, la bêtise n’étant jamais aveugle ni muette ? Chez Ben Slama, la puissance ou l’hypocrisie du collectif est souvent interrogée. Ses compositions articulent des figures archétypales au travers desquelles se distribuent des rôles séculaires et se reforme le théâtre social. Les relations entre individus, la loi et l’interdit, la norme et le tabou, les jeux de la séduction et du pouvoir travaillent de toute part ces spectacles tragi-comiques en attente de dénouements.

Marguerite Pilven

Art historian and philosopher